‘It couldn’t be him. It just can’t be. It must be someone else.’, was my first reaction when a common friend sent me a picture of his flower-decked bier lying outside his house in Jalandhar. I recalled Ashok Gupta reciting a Kafi of Baba Bulleh Shah at Zoji La pass where we saw a holy man being carried for burial.

बुल्ले शाह असां मरणा नाहीं गौर पया कोई होर

“It must be someone else, we ‘the immortals’ don’t die”, Ashok had said.

Years before he had said something similar when we had ‘together’ seen death at close quarters.

It was the month of June. Twenty-ninth read the date in the year 1985. By mid-night the temperature was 12 below zero. On the Tibetan plateau our altitude was 17,300+ feet. We were at the western edge of lake Manasarovar. We kiss-drank its partially frozen surface the next morning. Without gloves our hands were slowly turning blue. Strong easterly winds howled the earlier part of that night. I wonder how we survived that night amid nothingness. Yes, survived brutal cold, hunger, fatigue and the fear. The fear of having lost our way in the Himalayan desert. The fear that no one may come looking for us or consider us dead in that Himalayan moonscape. One more night out in the open would have meant certain death for the three of us. But, but Ashok had said “We can’t die here uninvited”.

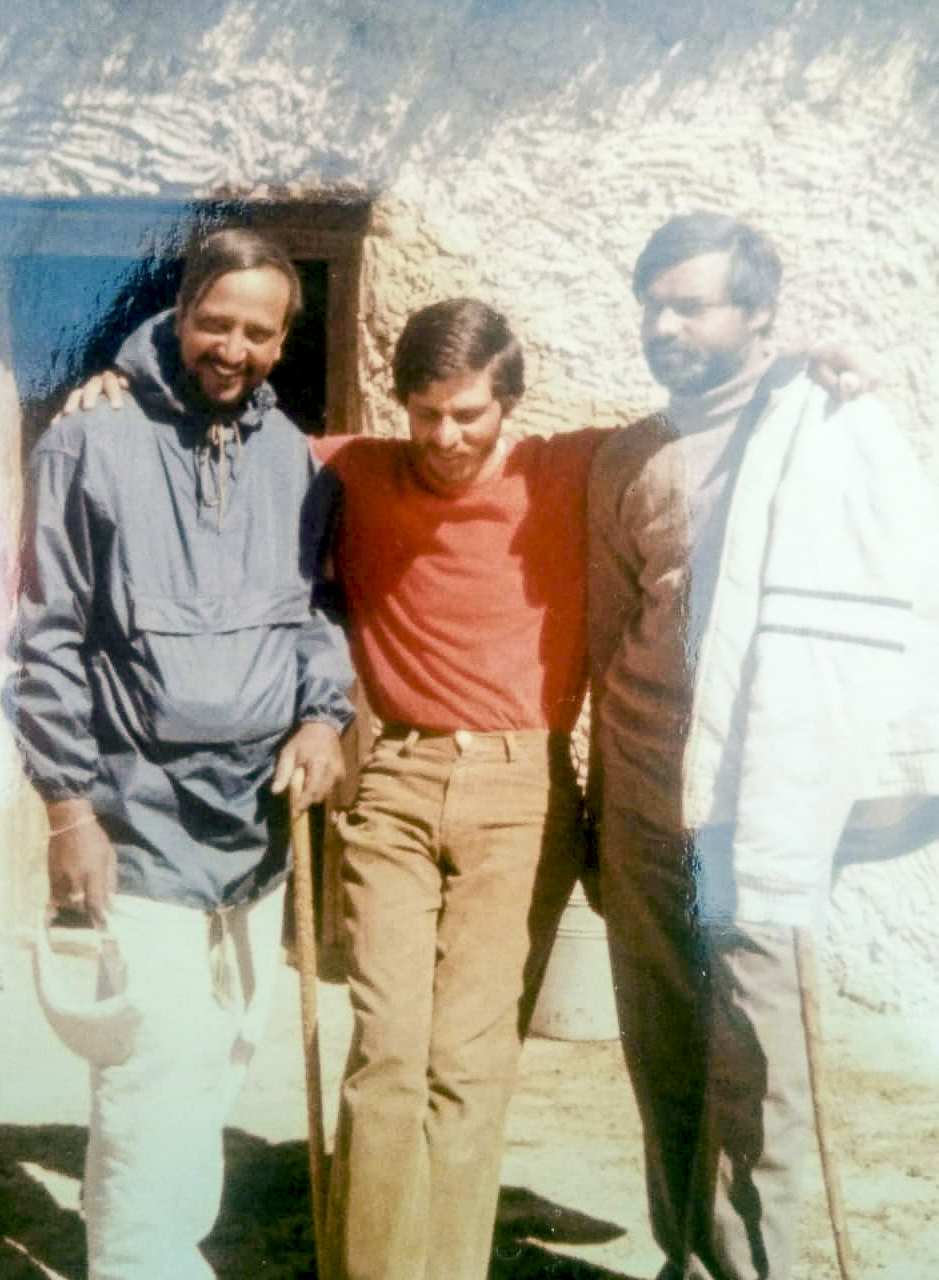

That night Ashok Gupta was wearing his trademark white kurta-pyjama, no thermals inside. The hood of his blue wind-cheater protecting his ears and head. Arun Singhal, our other friend was decently clad in a high neck sweater but not enough for that altitude or the open skies where a little more cold could have frozen us. Unless you are a Mongol nomad, a Tibetan herder or a Chinese military jawan you dont fools around Mt Kailash or Ghurla Mandhata ranges carelessly at night. We were not fooling around, we had lost our way.

Five other members of our group were accompanied by a Tibetan yak herder who was transporting our camping equipment. That night we clung to each other in a tight embrace to conserve body-heat, arms locked we jogged in-sync, we created a tight triangle of bodies using our breath to warm our chests and ward off the cold with our back, we pissed on our feet when our toes were freezing. We cursed ourselves but never once thought that we would die that night. The thought of death came only next afternoon when despite all our efforts we were not able to find the trail that would lead us to our campsite. Our batchmates were supposed to leave for the next campsite by noon. None of us had any communication equipment or anyone to guide.

The morning before was the most inviting one which lured us to make multiple mistakes. We decided to shed extra layers and trek leisurely around the undulating Barkha Plains. The day temperature tempted us to slow down our pace, rest more often, fish in streams, stop to photograph each Marmot peeping at us from its hole, admire and lure herd of Tibetan Wild Ass and the colony of white woolly hare. We were in the awe of the beauty, the sheer scale of the Himalayan plains where a hundred aeroplanes could land together. With no clouds and a bright sun that hurt during noon we enjoyed the stark contrast of the blue skies against white Himalayan peaks and stunning granite rocks. That morning, together, we had spotted a Brahminy Duck diving in Mansarovar for its catch. Ashok had said it was a good sign.

My brown corduroys, a wind breaker and a muffler around the neck worked well during the day but at night I was the worst clad. We hadn’t had a morsel since we left last camp and I was reminded of the Brahminy Duck all the time. How many fish it would have devoured that morning? We trudged up and down a dozen hills that evening before the Lords switched off the light in that stunningly beautiful playground for their ilk to sleep.

To reach our Himalayan Eden we traversed four major valley systems connecting India, Nepal, Tibet and China. We trekked over 129 km in 28 days, without a day’s break, crossing two high-altitude mountain passes one of which, Dolma La, was over 18,470 feet, braved treacherous crevices over unstable glaciers, were beaten down by winds and thunder, negotiated and forded near-freezing streams, glacial melts and rivers. We slipped around gorges; skidded off steep gradients; spent sleepless nights with minimal food; braved freezing winds, rain and snow but we survived. We survived our bursting lungs in rarified atmosphere, yes we survived this and dangers of many other climbs and high-altitude treks. Did we survive to die like this?

Sorry, I can’t say my Alvida, not yet.

गौर पया कोई होर

Yes, that must be some else.

outside Mt Kailash camp June 1985

You must be logged in to post a comment.