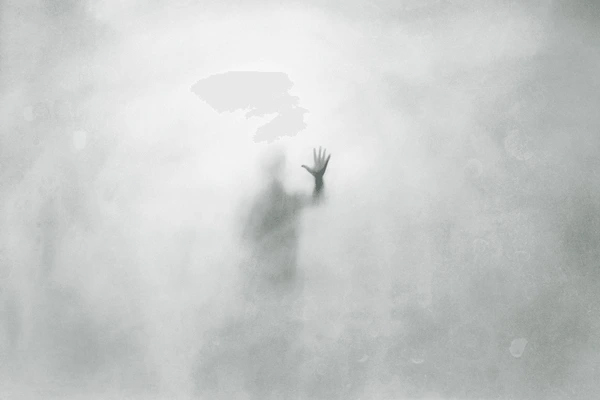

This day 752 years ago (30 Sept 1207 – 17 Dec 1273), one of the greatest Sufi mystic poet, and founder of the Islamic brotherhood known as the Mevlevi Order, RUMI (Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Rūmī) passed away leaving behind not just immeasurable wealth of mystic poetry and Sufi thought (falsafa) but a deep spiritual worldview relevant pretty much today. Sample this:

Where did the handsome beloved go?

I wonder, where did that tall, shapely cypress tree go?

The son of an erudite Islamic theologian, Rumi was encouraged to pray, fast, and study scripture as well as mathematics, philosophy, literature, and the languages of Persian, Arabic, and Turkish, all of which shaped his worldview and eventually his poetry. Rumi would follow in his father’s footsteps to become a theologian in Konya, offering sermons to thousands, until around the age of forty when Shams of Tabriz, an itinerant Sufi mystic, drew him from the pulpit into a life of poetry and music. You must read more of Rumi’s life and his poetry which is simply phenomenal. Check this piece by Haleh Liza Gafori for New York Review Books at https://lithub.com/a-mystic-a-poet-an-old-friend-haleh-liza-gafori-on-the-enduring-power-of-rumi/

To his poem Where did the handsome beloved go? Rumi adds

He spread his light among us like a candle.

Where did he go? So strange, where did he go without me?

All day long my heart trembles like a leaf.

All alone at midnight, where did that beloved go?

Go to the road, and ask any passing traveler —

That soul-stirring companion, where did he go?

– Translated By Brad Gooch & Maryam Mortaz

You must be logged in to post a comment.